Tossols Basil

Trees on the pitch

Tossols Basil Athletics Stadium

Tossols Basil

The area called Tossols Basil, which is designated for leisure activities, is located at the edge of both a city and a natural park along a river. When contemplating adding sports facilities here, the architects faced a dilemma of either clearing large amounts of slow-growing oak trees or succumbing to environmentalists who wanted no change at all.

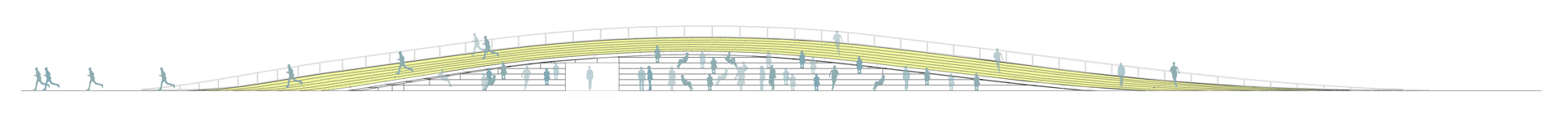

The solution was to site the athletic track in a forest clearing, previously used for cultivation. Nature and sports are united and runners appear and disappear as they make their way around the track. The project highlights the beauty of the landscape and preserves the vegetation as a filter that changes with the seasons.

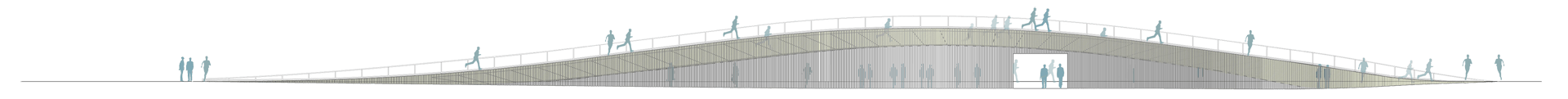

The seating for observing the athletes is developed as small terraces or embankments between the clearings, often using the natural topography. The slender lighting towers become points of reference in the landscape.

Natural surroundings

Set in natural surroundings, this athletics track enables the merits of the existing landscape to be emphasized and the track events themselves to be brought closer to nature.

The track is implanted in two clearings in the white oak wood. Contiguous woodland at a distance and far-off woodland are the relations established between the track and the wood, the seating being developed as small terraces or as embankments between the clearings.

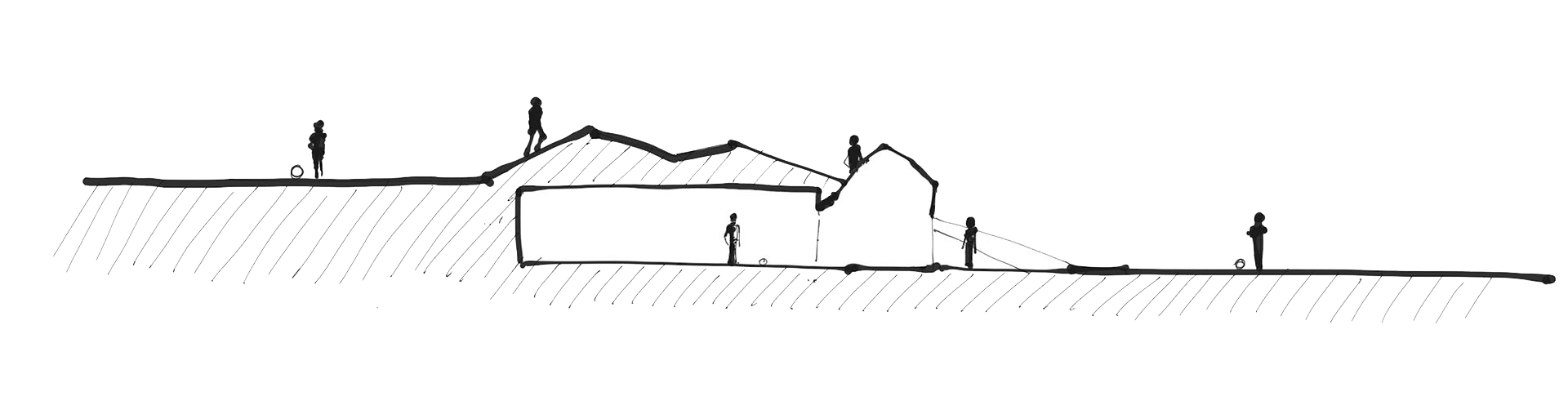

As well as containing the functional facilities, its equipment is interrelated with the walls, embankments and ramps that formalize the change in height from entrance to track; it is the great gateway directed towards the races, a filter between nature and the urban. A gateway that is an extended roof held up by two volumes, one of which is like a great open window with a glass wall which doesn’t interrupt the visual continuity and picks up the reflection of the wood that has determined the entire intervention.

Architect

RCR Arquitectes Rafael Aranda, Carme Pigem, Ramón Vilalta Marià Vayreda, 23 ES — 17800 Olot

Team

M.Tàpies, A.Sáez, M.Bordas, Brufau, Obiol, Moya. G.Rodriguez, P.Rifà

Client

C. Bisbe Guillamet

Building contractor

C. Joan Maragall

Address

Carrer Cadis, 35 17800 Olot Es — Girona, Spanien

Aerial view

Thank you, Google!

Photograph

H.Suzuki, E.Pons, M.Checinski

Author

RCR Arquitectos

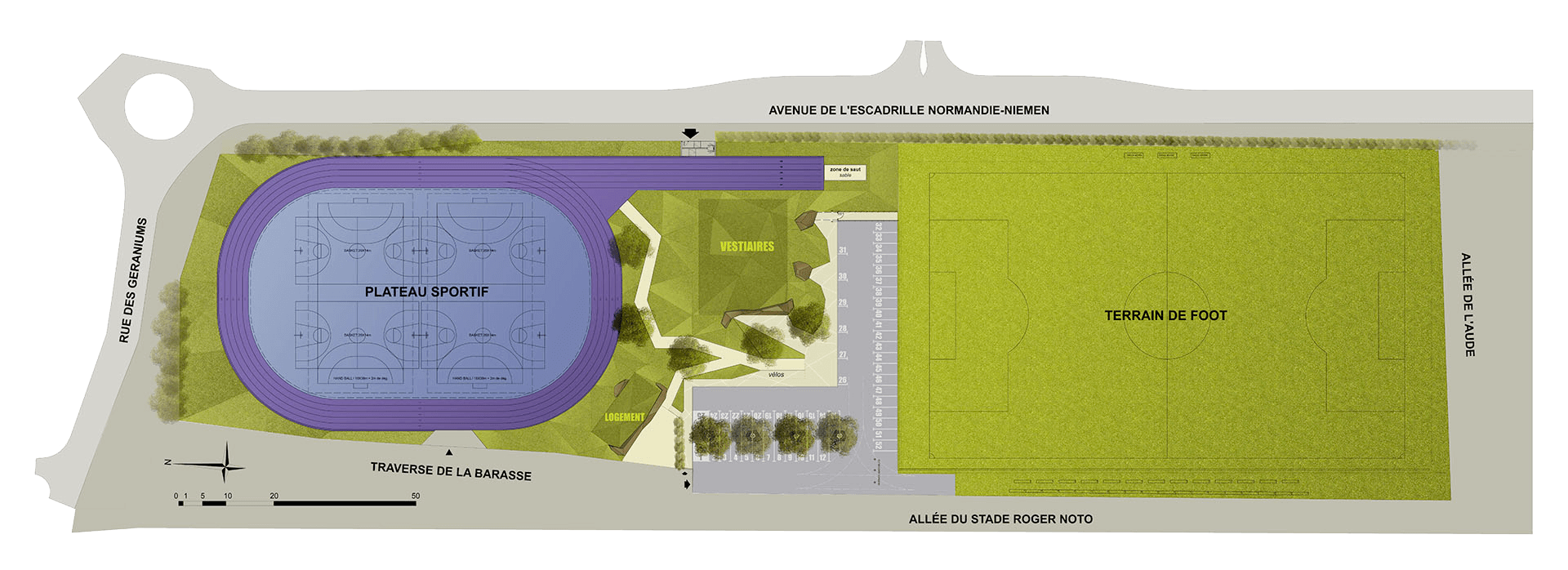

Site plans

The beauty of steel

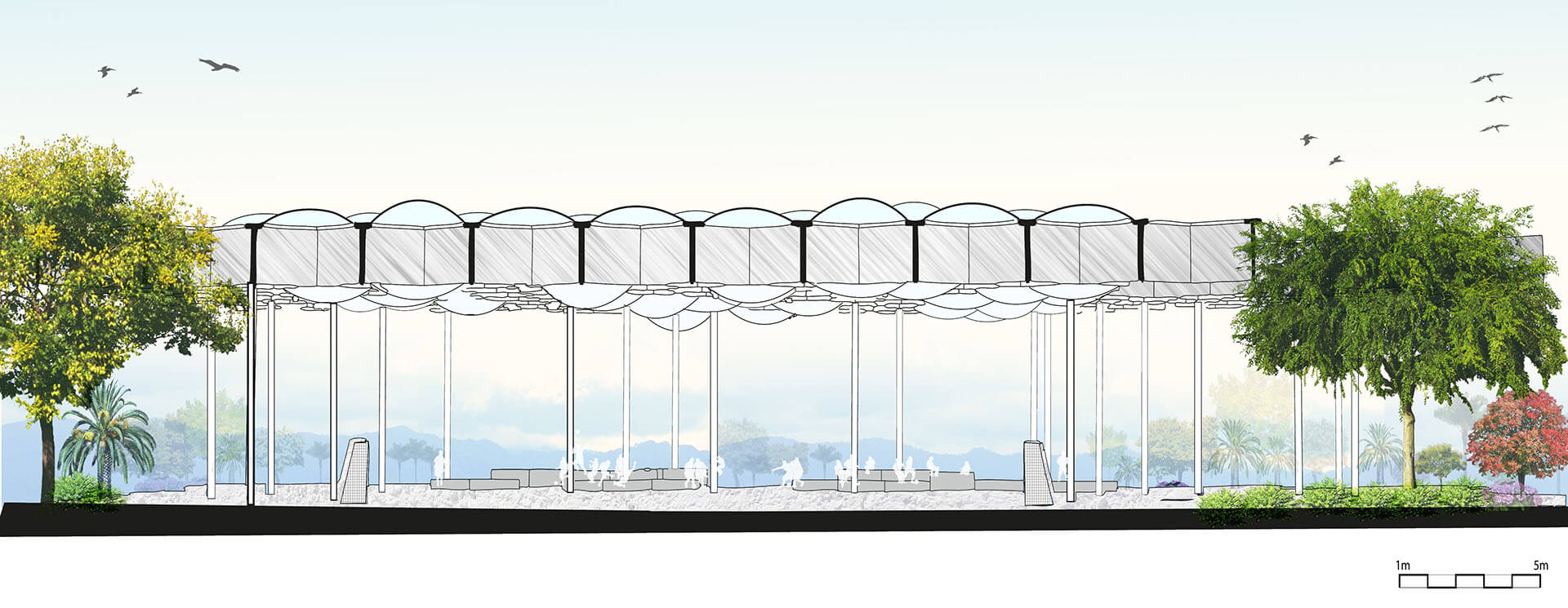

After completing the track in 2001, other facilities have been added; a soccer field and an entrance pavilion with changing facilities, that RCR calls the 2x1 pavilion. This structure that acts as a gateway to the area has a thin roof supported by two volumes allowing multiple views through.

Once again, RCR employs only one material – Cor-Ten steel – and the structure settles easily into its natural setting.

Running, nature and Pritzker

Set in natural surroundings, this athletics track enables the merits of the existing landscape to be emphasized and the track events themselves to be brought closer to nature.

The track is implanted in two clearings in the white oak wood. Contiguous woodland at a distance and far-off woodland are the relations established between the track and the wood, the seating being developed as small terraces or as embankments between the clearings.

As well as containing the functional facilities, its equipment is interrelated with the walls, embankments and ramps that formalize the change in height from entrance to track; it is the great gateway directed towards the races, a filter between nature and the urban. A gateway that is an extended roof held up by two volumes, one of which is like a great open window with a glass wall which doesn’t interrupt the visual continuity and picks up the reflection of the wood that has determined the entire intervention.