Game-Changing

Eye-Tracking Studies Reveal

How We Actually See Architecture

Form follows function

While many architects have long clung to the old “form follows function” adage, form follows brain function might be the motto of today’s advertisers and automakers, who increasingly use high-tech tools to understand hidden human behaviors, and then design their products to meet them (without ever asking our permission!)

Biometric tools like an EEG (electroencephalogram) which measures brain waves; facial expression analysis software that follows our changing expressions; and eye-tracking, which allows us to record “unconscious” eye movements, are ubiquitous in all kinds of advertising and product development today—beyond the psychology or medical departments where you might expect to see them. These days you’ll also find them installed at the behavioral research and user experience labs in business schools such as American University in D.C. and Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) in Massachusetts.

What happens when you apply a biometric measure like Eye-Tracking to architecture? More than we expected…

Indeed, after running four pilot-studies looking at buildings in both city and suburb (New York City, Boston, Somerville and Devens, MA) since 2015, we think these technologies stand to revolutionize our understanding of how architecture impacts people and, in a first, allow us to predict human responses, including things like whether people will want to linger outside a new building or, within fractions of a second, choose to flee. (There’s more on our first Eye-Tracking study in the cover story of Planning Magazine, June, 2016.)

In sum, we believe once you “see” how we look at buildings, you’ll never look at architecture the same way again. So, here are three unexpected findings gathered from Eye-Tracking architecture:

Author of text

Photographs

Ann Sussman

Thanks to

- Common Edge, the original place this article appears

- Boston’s Institute for Human-Centered Design

- The Devens Enterprise Commission

- Prof Justin B. Hollander and Hanna Carr ‘20, Tufts University as a contributing researcher. His research and funding allowed two of the studies (NYC + Devens) to proceed

- Dan Bartman, City of Somerville Planning Department for invaluable assistance and research support

- For game-changing technological tools many thanks to iMotions and 3M VAS and their staff for making this type of research possible.

-

People ignore blank facades

Run even one Eye-Tracking study and this result will hit you on the head like a ton of bricks. Put it in red lights: People don’t tend to look at big blank things, or featureless facades, or architecture with four-sides of repetitive glass. Our brains, the work of 3.6 billion years of evolution, aren’t set up for that. This is likely because big, blank, featureless things rarely killed us. Or, put another way, our current modern architecture simply hasn’t been around long enough to impact behaviors and a central nervous system that’s developed over millennia to ensure the species’ survival in the wild. From the brain’s visual perspective, blank elevations might as well not be there.

You can see this in the study above. It shows two views of NYC’s Stapleton library, one with existing windows, at right and, at left, one without them (a photoshopped version we made of the same facade). The bright yellow dots represent “fixations” that show where eyes rest as they take in the scene in a 15-second interval; the lines between are the “saccades” that follow the movement between fixations. On average, viewers moved their eyes 45 times per testing interval, with little to no conscious effort or awareness on their part, and no direction on ours. In the image at left, without windows, test-takers more-or-less ignored the exterior, save for the doorway. This is not the case with the image at right. The photos below show heat maps which aggregate the viewing data of multiple individuals. These maps, glowing brightest where people looked most, suggest how much fenestration patterns matter: they keep people fixating on the facade, providing areas of contrast the eyes innately seek and then stick to. Again and again, our studies found that buildings with punched windows (or symmetrical areas of high contrast) perennially caught the eye, and those without, did not.

-

Fixations drives exploration

Why does it matter where people look without conscious control? That’s the ultimate question. In the course of our research, we picked up a cognitive science mantra, “fixations drive exploration,” and learned that unconscious hidden habits, such as where our eyes “fixate” without conscious input, determines where our attention goes and that’s hugely significant. Why? Because unconscious fixations in turn direct conscious activity and behavior. No wonder Honda and GM use this technology. No wonder advertisers of all stripes do too. They want to know where we look so they can manage our behavior, making certain an ad grabs attention as intended, before it’s released. They want to manage our unconscious behavior so they get the conscious outcome they desire from our brains, (without having to lift a metaphorical finger!)

And what about architecture?

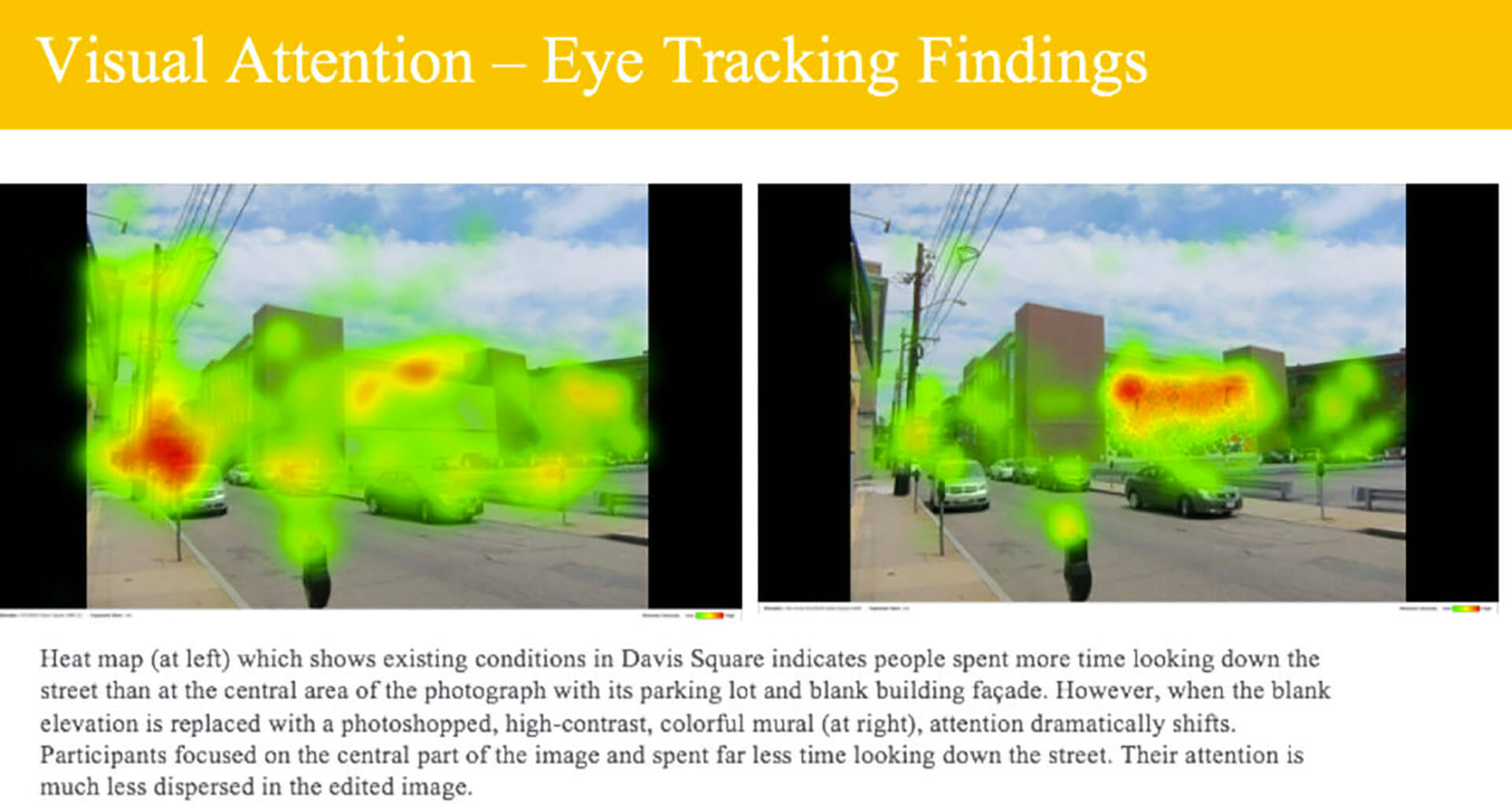

Eye Tracking can help us untangle the fraction-of-a-second experiences that drive our actions around buildings in ways we may never realize. To see how our “fixations drive exploration,” let’s take the scene above; at left is Davis Square in Somerville, MA, a dense residential district near Cambridge, home to many colleges and businesses. At right, the image shows a photoshopped version of the same scene. In the past year we’ve asked more than 300 people at lectures where they’d rather stand and wait for a friend: in front of the blank building or in front of the building with the colorful Matisse-like mural. Amazingly—without even talking with one another—everyone picked the same place, standing in front of the mural.

Why?

Turns out eye tracking suggests some interesting answers. The heat map above indicates that the mural provides fixation points to focus on; these give us a type of attachment we like and seem to need to feel at our best; without these connections people apparently don’t know where to go—they get anxious—and so won’t select the blanker site. Amazing the power of fixations to drive exploration whether in ads or architecture. (I guess it has to be this way since we only have one brain.)

-

People look for people, continually

And finally, ironically, the most important thing Eye Tracking studies of architecture revealed to us had nothing to do with buildings at all. Instead it suggested how much our brain is hardwired to look for and see people. We’re a social species and our perception is relational. In other words, it’s specifically designed to take in others. Eye-tracking studies bear this out, repeatedly. Yes, architecture matters, but from our brain’s perspective, people matter more. No matter where they are.

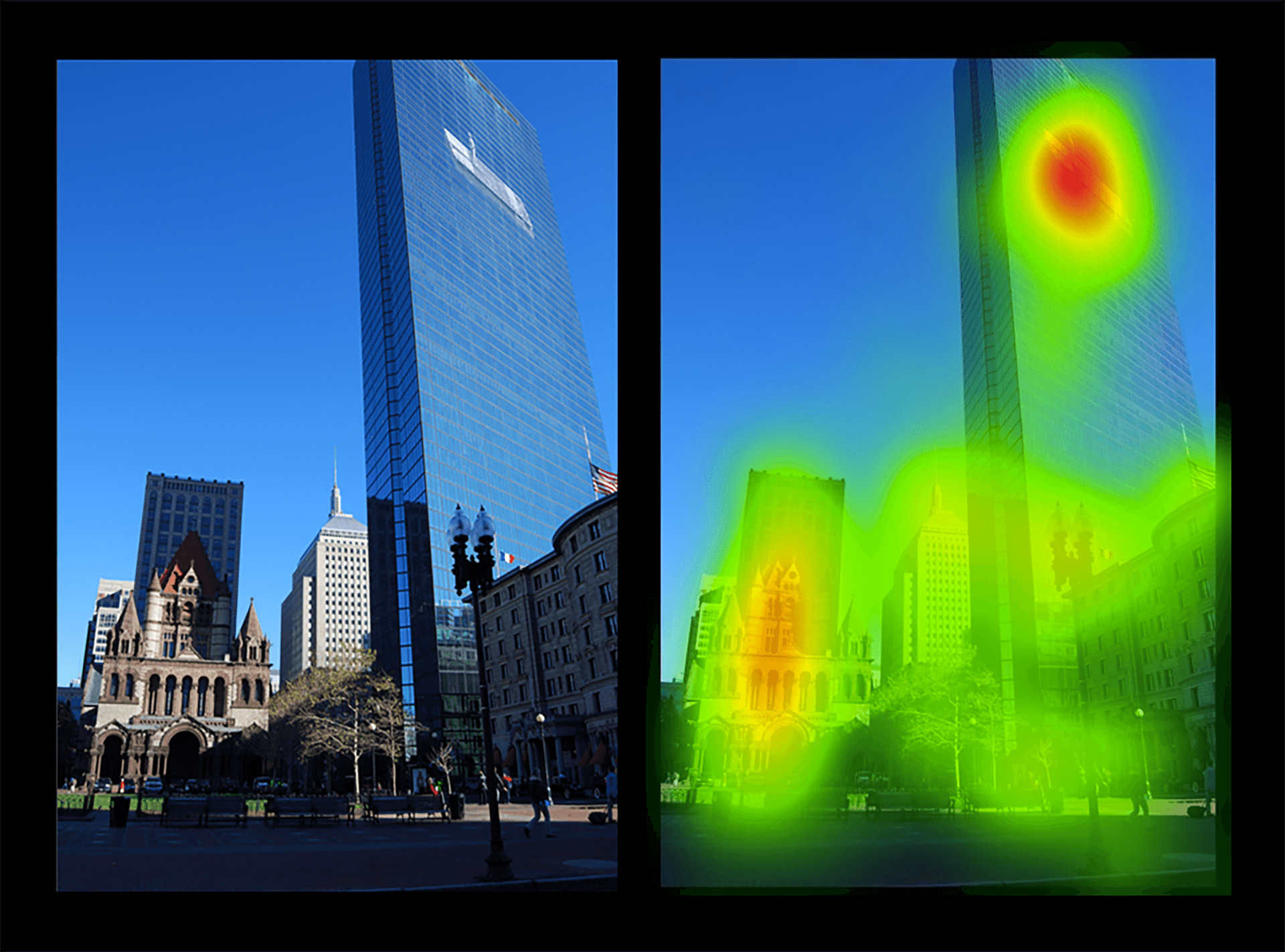

We saw this eye tracking Boston’s famous Copley Square with its historic Trinity Church (c. 1877) and equally historic Hancock Tower (c.1976), which recently changed hands and is now called 200 Clarendon (see images above). In 2015, the tower featured a temporary art installation of a man standing on a floating barge. Guess where people looked?

If you chose the small silhouette of the guy, you’re right. Richardsonian Romanesque has its appeal, and there may be die-hard modernists out there, but when it comes to human bodies, that’s what your brain wants you to focus on. (See reddest heat map.) That’s where people went to look; otherwise, they barely gave the glass building a glance; it simply can’t provide fodder for focus from a brain’s 3.6 billion-year-old perspective.

If there’s one all-encompassing conclusion, it’s this: we can only hope to save ourselves if we know what we are. Evolution is real and we’re artifacts of the process. Eye-tracking architecture shows ancient algorithms directing us even though we can’t perceive them. Architecture that’s humane engages our animal nature acknowledging our remarkable history. In terms of how we take in the world, our ancestors learned the hard way to immediately look for areas of high contrast and other creatures, particularly faces, and they passed the life-saving traits on to us. These behaviors will not go away soon.

So we find ourselves today, modern man, riveted to looking at the silhouette of someone outside the 35th floor of a high-rise. It truly makes no sense, unless you consider where we came from and the struggle for survival that made us.

Ann Sussman

is an author, architect and biometric researcher. Her book Cognitive Architecture, Designing for How We Respond to the Built Environment (2015), co-authored with Justin B Hollander, won the EDRA award for research in 2016. More info at: annsussman.com and her blog, geneticsofdesign.com.

FIVE ANSWERS

- Please tell us about your top 5 sports facilities.

There’s one sports arena that’s been part of my life forever: The Roman Colosseum! My mom found a print of it by Piranesi when I was a kid and we lived in Europe; it came back with us to the United States where she placed it in the living room; today that same print adorns my dining room. Answering these questions made me realize for the first time that a 2,000-year-old amphitheater is the one building I’ve been looking at most of my life! - Which architects and buildings have left a lasting impression on you? Why?

The other building that definitely left a lasting impression on my brain is Palladio’s Villa Rotunda, or Villa Capra in Vicenza Italy. I fell in love with it in when first studying architecture. I even took Palladio’s plans to a local baker when I got married for the design of my wedding cake! This building influenced the design of countless other buildings around the world, including in the U.S., The White House. And the Palladian facade of the American President’s home is today on U.S. currency (every $20 bill). I couldn’t understand why a country estate designed for a wealthy, retiring Vatican cleric in the 16th century (a party pavilion !) could come to represent American democracy! So we eye tracked the villa – and got an intriguing answer: In pre-attentive processing (the first 3–5 seconds you look at something) the villa suggests a face! And because of our brain’s mammalian attachment wiring, no other image can grab us like that – and no other pattern ever will. - What and whom do you consider as industry trends and trendsetters?

Key industry trends in architecture include the drive to sustainability, designing to promote human health and wellness and new findings in cognitive science which help us understand what our brain is set up to see. For more information on the latter, please see our website: geneticsofdesign.com. - What book should architects in this industry absolutely read?

I’d have to recommend the one I co-authored with Tufts University professor Justin B. Hollander, Cognitive Architecture, Designing for How We Respond to the Built Environment (Rutledge, 2015), and one by a Nobel-prize winning neuroscientist on why art works: Eric Kandel, The Age of Insight (2012). There’s also a good little book on the brain by Oxford University Press: The Brain: A Very Short Introduction, by Michael O’Shea. - What is/was your favorite song to listen to while designing?

Favorite song to listen to while writing or meeting with others to discuss research ideas would have to be the buzz of a local cafe; the murmur of people talking and the clinking of the coffee cups is somehow very soothing and gets me to think at my best.

Janice M. Ward

is a writer, designer, blogger and STEM advocate. She and Ann Sussman co-authored the cover story in Planning Magazine’s 2016 June issue: using eye tracking and other biometric tools to help planners shape built environments. More info at acanthi.com and geneticsofdesign.com.

FIVE ANSWERS

- Please tell us about your top 5 sports facilities.

As a native Bostonian I’m drawn to Fenway Park, which is listed as one of the 10 Most Historic North American Stadiums. It’s the local, sentimental favorite. - Which architects and buildings have left a lasting impression on you? Why?

For our 20th anniversary, my husband and I visited Frank Lloyd Wright’s Falling Water. Breathtaking. Not comfy by today’s standards, but amazing. Imagine a 5300 square foot house built over a waterfall complete with internal greenhouse and stairs leading down to the stream below. - What and whom do you consider as industry trends and trendsetters?

Architecture should keep up with changes in technology. Not just building technology. Design schools should integrate Science, Technology, Engineering, Math (STEM) initiatives including neuroscience, biology, computer science and biometric tools to develop people-centric, data-driven environments. - What book should architects in this industry absolutely read?

Technology moves so fast, I tend to read online content in websites, blogs and magazines. Two favorites are Architectural Recordand Dwell. The book I am currently enjoying is “The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate” by Peter Wohlleben. - What is/was your favorite song to listen to while designing?

While writing, I often listen to Bach, Eliot Fisk or Andre Segovia. Gentle, instrumental music inspires without distraction.